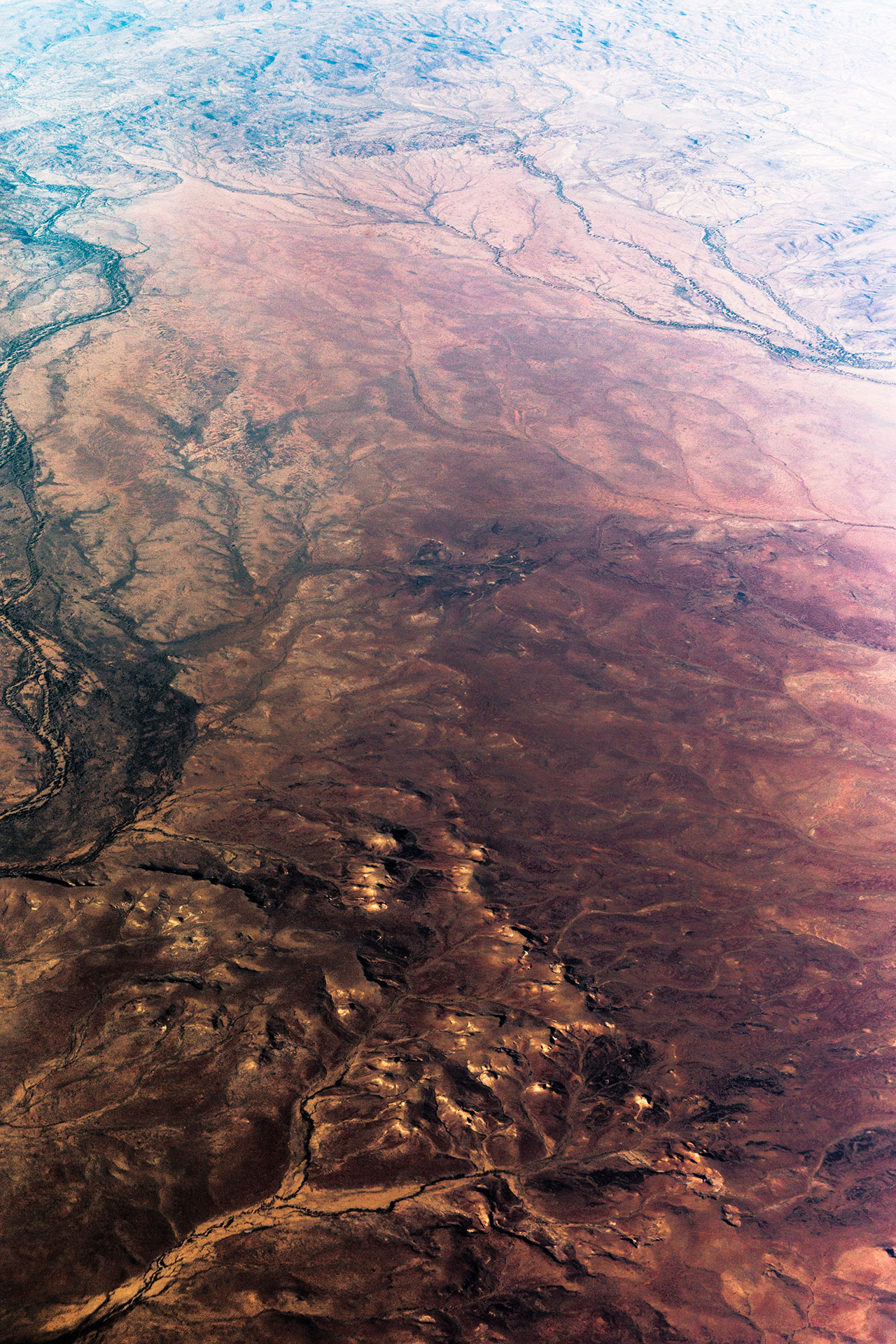

Munga-Thirri is a series of hyperrealistic aerial landscape photography captured above Munga-Thirri National Park formerly known as The Simpson Desert, Queensland, Australia.

Munga-Thirri stretches across over 175,000 km², which all experience extreme high and low temperatures throughout the year. Home to 180 species of birds, this habitat also harbours life for dingoes, geckos and feral camels. Not even some of Australia's most stereotypical animals can survive out here. You can see how the desert has been left without a drop of moisture. This dryness is due to the wide variety of desert flora and fauna leaving the region barren.

Like any time you peer out the portal of your airliner window seat, you’re greeted with an unexpected view of a place you’ve likely never been. When I raised the shutter after a highly disrupted slumber, I was witness to one of the most intense bands of light pouring across the top of the horizon. My energy was quickly restored as it was clear this was going to be a gorgeous sunrise. I could not hold myself back from reaching for my camera in the stowed away luggage compartment. The vastness of what I was experiencing could not be translated into words.

The landscape continually kept unfolding extraordinary sights where the distance I had traveled away from home really started to become more apparent. This never ending habitat seemed to grow simultaneously with my amazement as our destination was unknowingly drawing closer. On reflection, this segment of my commute all seemed to fade into one while I looked straight down at the landscape where time simply disappeared. That’s when I know I’m truly in my element and subsequently heading in the right direction. I never wanted it to end and I wonder if anyone else onboard or down on the ground, present or past, felt the same way.

An except from Munga-Thirri 2/10 (2018)

Upon reviewing my photography session capturing the landscape below, I noticed a common theme forming. At first it wasn’t obvious but after some time familiarising myself with my subject, I became to recognise the visual representation on the earth’s surface and how it would have challenged the people that belong to these terrains. This sensation of sitting high above, gliding home without a care, gave me that eye opening realisation about how we take our own survival for granted. I set out to evoke a feeling of surprise and amazement in the viewer just like my own. I want the viewing experience to spark a notion of discomfort in an otherwise abundant and spiritual setting. It is my intention to blur the lines of aerial photography as only a platform and its purpose to document the exploration and artistry in the landscape. Connecting these genre types is absolutely integral to telling this environments magnificent story.

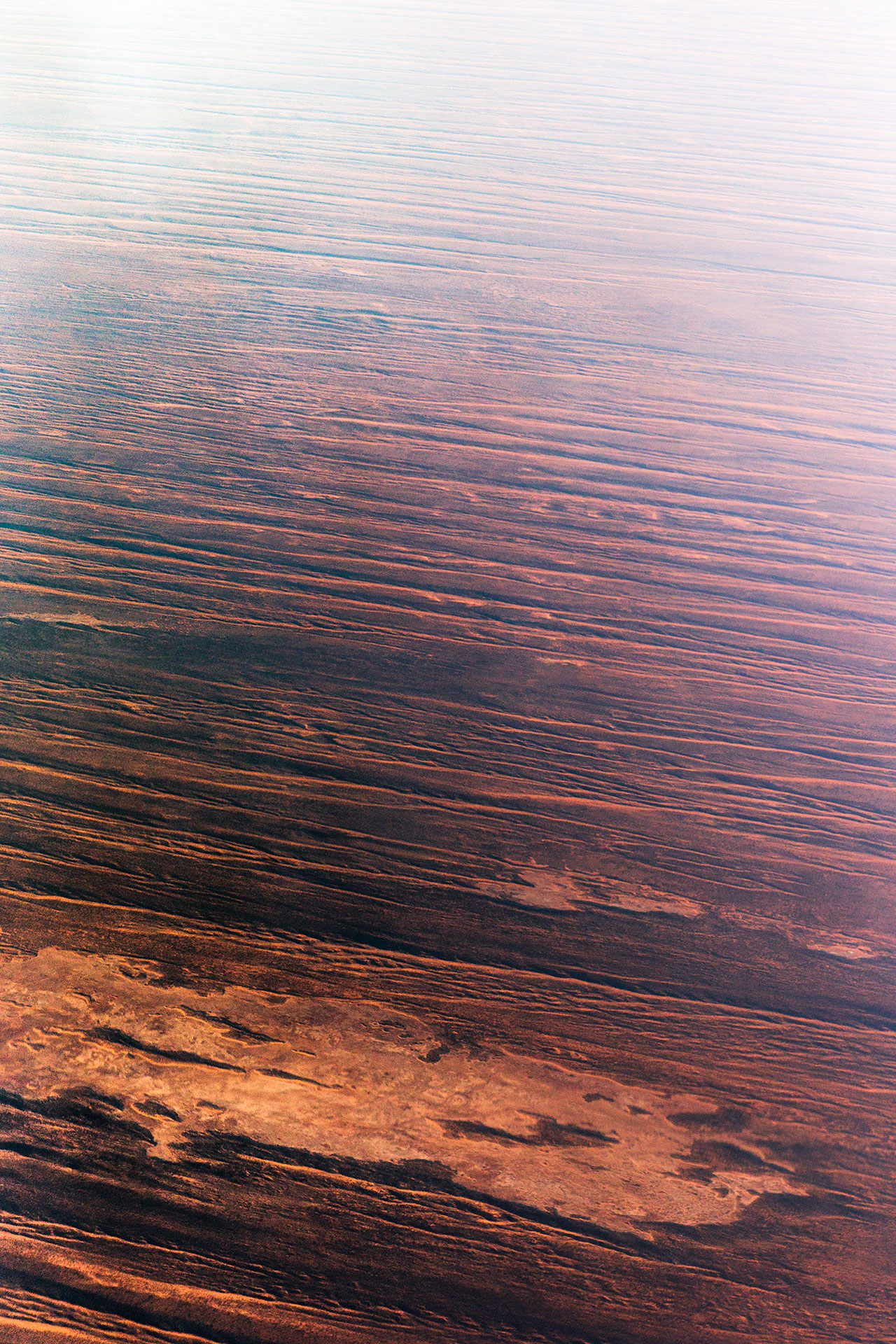

I want to share how my surroundings collected themselves so the eye can explore how the harsh topography interacted with the temperature fluctuations on the surface. From the ground to the sky, I began to notice how each step became a little colder. Being caught behind an aircraft’s screen gave me only one option, to photograph through the imperfections in the glass and use them to further enhance what I was already seeing on the ground. This typically unsatisfactory distortion then amplified the extreme attitude of colours that graduated throughout the earth’s surface.

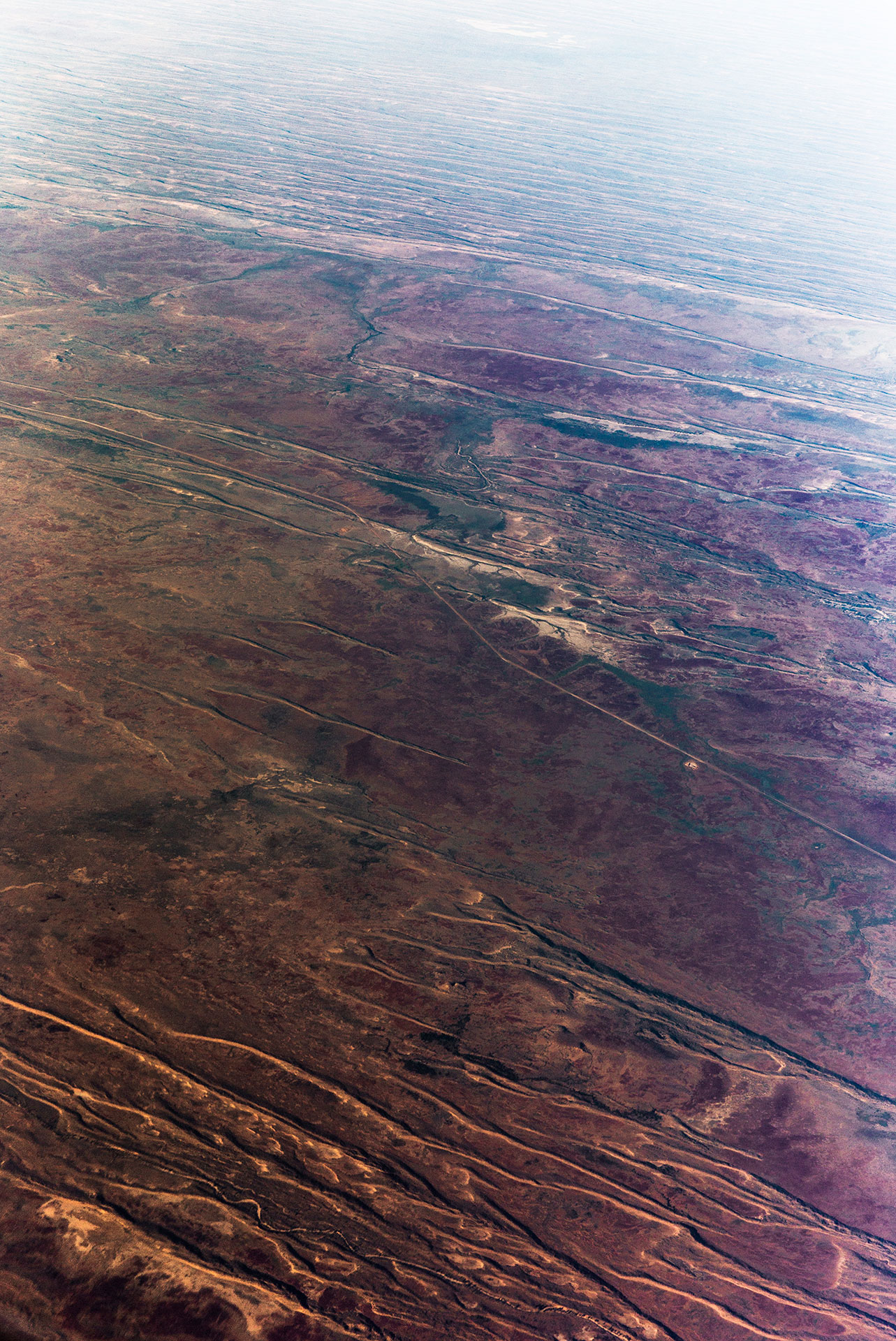

By my estimate, thanks to in-flight GPS information, I was facing directly west towards Alice Springs. The sun began to rise from the opposite side of the aircraft and refracted light skimming across the dynamic sandy plains of central Australia. This is precisely where the landscape made an abrupt change.

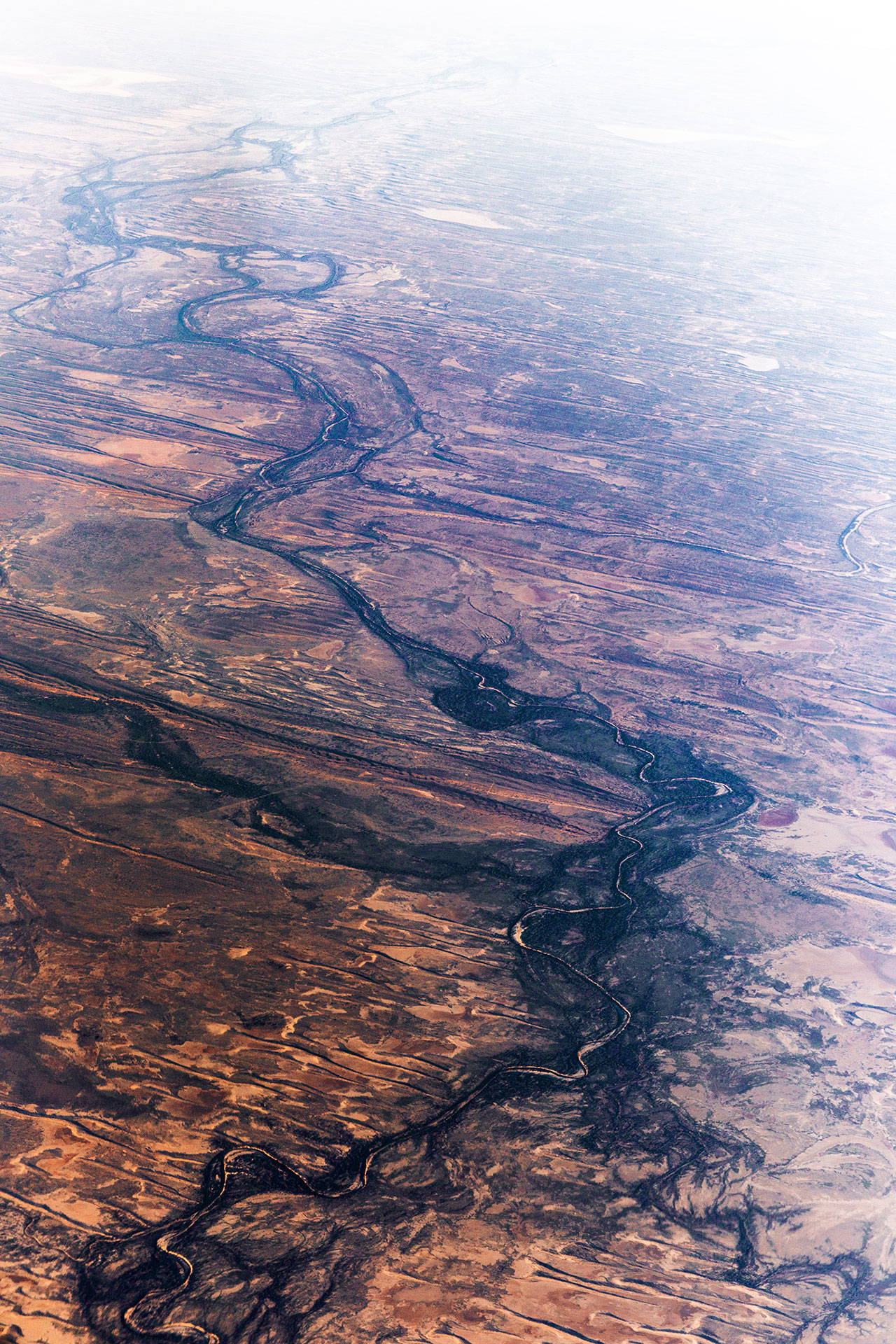

Large sand dunes in the region can measure up to 50 meters in height and 1 km apart. Most dunes started forming 30,000 years ago and have now shifted their way into completely different formations that have expanded to roughly 200 km in length. The dune systems comprise of spinifex grasslands, acacia woodlands and extensive playa lakes. Each of these networks combined with seasonal rainfall contributes to the soaking up of water from underground springs. In the summer of 2017 the National Park was closed due to extreme temperature conditions reaching over 50°, preventing any emergencies or evacuations of the 10,000 visitors that would otherwise visit. It is since recommended to exclude summer as an season to visit this remote destination.

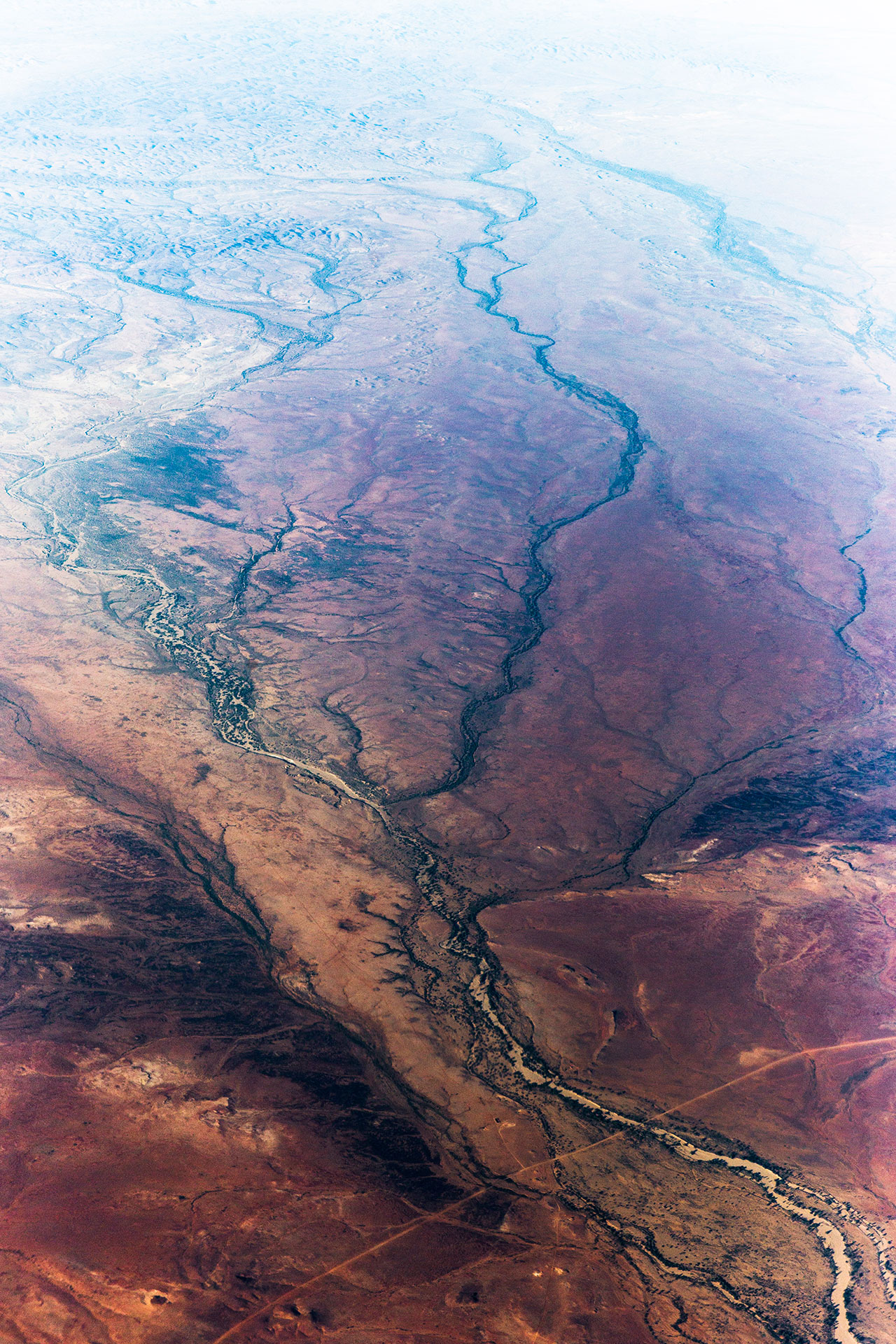

It is with great pleasure to acknowledge and pay respect to the traditional owners from the Wongkamala & Pitta-Pitta tribes for their commitment to learning and understanding from their harsh environment. For generations, Aborigines have lived in this region without any assistance from the modern world. Communities of all sizes survived in these dry conditions by digging soaks up to 7 meters deep providing cool dark spaces during severe heat waves.

An except from Munga-Thirri 8/10 (2018)

As the sun rose, the landscape was never repeated, every rise and fall offered a new perspective of the environment. However, the best way to navigate this vast landscape is by following the stars at night. This is how aborigines travelled throughout this arid landscape. They told their stories, passing them down with knowledge and information to the following generations solely through oral history.

Today’s modern technology has generated its own juxtaposition between the past and the present. Whether you’re using the beautiful starry night sky or your mobile device to navigate your way, every destination is essentially a journey that translates into a story. This mirrors itself exactly from the physical world into the metaphorical. These two attributes then connect us to our final destination and its overall purpose or newly discovered understanding. These very historical and modern events that have taken place create a spiritual state for those involved on the ground surface as well as high in the sky.

Flying 35,000 feet above this amazing place presents two views. The first view is the physical view of the terrain; patterns, chiaroscuro and intrigue forming an undulating topography only visible from the sky. The second is the holistic view. When I looked down through the window I found myself thinking not only about how stunning the scenery was but how tough the journey for traditional land owners must have been. How they learned to survive, grow and embrace this astonishing landscape is something I truly find fascinating.

There is an ancient myth about how these places were constructed by the great Rainbow Serpent. It formed these very rivers, valleys and ravines thousands of years ago. These stories like many others help us understand where this culture and heritage comes from but also the means of keeping it alive. There is so much knowledge attached to these tales from generations past that it has to be documented and shared for it to truly remain. I hope that even as a non-Aboriginal that local communities accept this body of work as it’s own contribution from my modern day perspective.

I find aboriginal artwork incredibly inspiring which holds a strong narrative of the earth and shared spirituality. It’s this that allows for a stronger connection with being Australian and your countries true history. This inspiration replenishes the things I love to do most in life, which is to discover and document new things, new places and spaces from a perspective that some might never have the privilege to see for themselves. The first and only requirement is to have my camera handy, after that, I can never predict the conditions, or in this case, the route, but I can make subtle adjustments to my overall plans in order to possibly have a chance to witness some of nature's most incredible sights. Like the many stories before us, I feel that it is very important to capture records like the ones in this series as they supplement the experiences of moments that otherwise only exist in our memories.